Dark Timber

Karsh-Masson Gallery

Ottawa, ON

October 6 -November 22, 2011

Through the investigation of a link between the human and the animal, Dark Timber examines the culture of disassociation and fear that has seeped into everyday life. In response to this fear, and as a means of protection, Dark Timber seeks to reconnect the viewer with the notion of communities and families as tightly woven, intricate networks. It is the acceptance, inclusion, and embrace of a place and a people acting as a community that dissipates a looming threat. The result is not an inherent abjection, but a means of escape from the constraints of contemporary Western society.

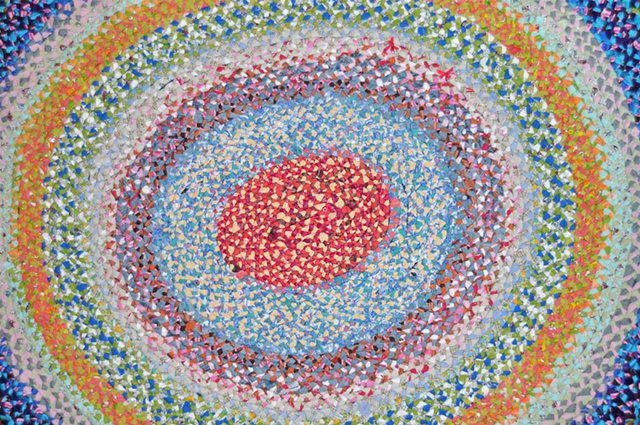

Dark Timber provides a momentary snapshot of when cornered, vulnerable beings step into a space—a simple rug that symbolizes a whole community—and are shielded. Instantly, the fawns have gained the permanence, weight, and strength of bronze, while the once lethal arrows have turned to glass. The fawns are unwavering and alert, aware of the impending threat but secure in the presence of their community.

In an act of reclamation and rejuvenation to the frayed bonds of community that have become an accepted reality of modern life, I collected old clothes—and in doing so a narrative of interwoven lives—from throughout my own community. I drew from a deeply rooted North American pioneer tradition of making braided rugs in order to create a protective sanctuary for the vulnerable and marginalized within a community. Using gathered scraps of old clothing, women would sit together to wind the strips into braids and then sew them into rugs in a constant effort to protect their families from the drafty houses. At a time in history when populations eked out a harsh existence from the land, resourcefulness, community, communication, and family were integral for survival. This rug is not simply made of clothes, it is a gathering of moments mined from our foundations. Moments cherished, held close, buried deep, pushed to the back of the closet, and forgotten over the years—tragic and celebratory, quiet and reverberating. Here they lie together as a tapestry of lives passed.

The term “dark timber” refers to a stand of coniferous trees in which deer feel deeply secure, and thus where they sleep. These trees stand as sentries around the sleeping animals and provide a thick cover from any passing predator, much in the same way one generation protects the next in healthy communities. In this scene we, the viewers, have become the trees, the dark timber, surrounding the fawns in a protective embrace within the gallery space.

The animal has become my closest artistic ally and animator in a life lived on the margins. I find myself drawing comparisons between an artist’s existence and that of the contemporary animal. We are out of step with the rest of the population, partly by choice and partly pushed; we are on the fringes looking in. As society vaults forward, both the artist and the animal find themselves sharing a common future—not of our making but one in which we play an integral role. We are both a witness and the provider of representations of harsh and unforgiving realities—a way of life that can only be sustained through the support and presence of these brightly coloured, roughly hewn, and often unexpected communal bonds.

Today, the animal exists as spectacle, a raw material, a commodity, and an exploited entity whose fate is forever bound to ours, simultaneously revered and threatened by a human presence. However, upon returning their gaze, we become aware of our own humanity. This gaze traverses the abyss created through the lack of language and abuse of power. It reminds us of what we have lost in our passage from nature to culture, of the conspicuous absence of the unburdened animal in contemporary society. The blurred boundaries and conflicted identity articulated in the artistic investigation of the animal as Other now exists as a mass of contradicting realities that manipulates the representation of the animal in order to express a shared cultural trauma and the myth of innocence. Our true selves are hybrid beings, neither this nor that, an animal that exists in the in between—in the gap between nature and culture, man and woman, ethics and exploitation, sex and violence, creation and destruction, human and animal, Eros and Chaos.